Content on this webpage is provided for historical information about the NIH Clinical Center. Content is not updated after the listed publication date and may include information about programs or activities that have since been discontinued.

Twenty-five years ago, experts at the NIH Clinical Center, along with colleagues from the National Cancer Institute and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, performed the first gene therapy in the US. On Sept. 14, 1990, a team of researchers, nurses and other dedicated staff administered the novel technique that uses genes to treat or prevent disease.

Gene therapy involves replacing a mutated gene that causes disease with a healthy copy of the gene; inactivating, or “knocking out,” a mutated gene that is functioning improperly; or introducing a new gene into the body to help fight a disease.

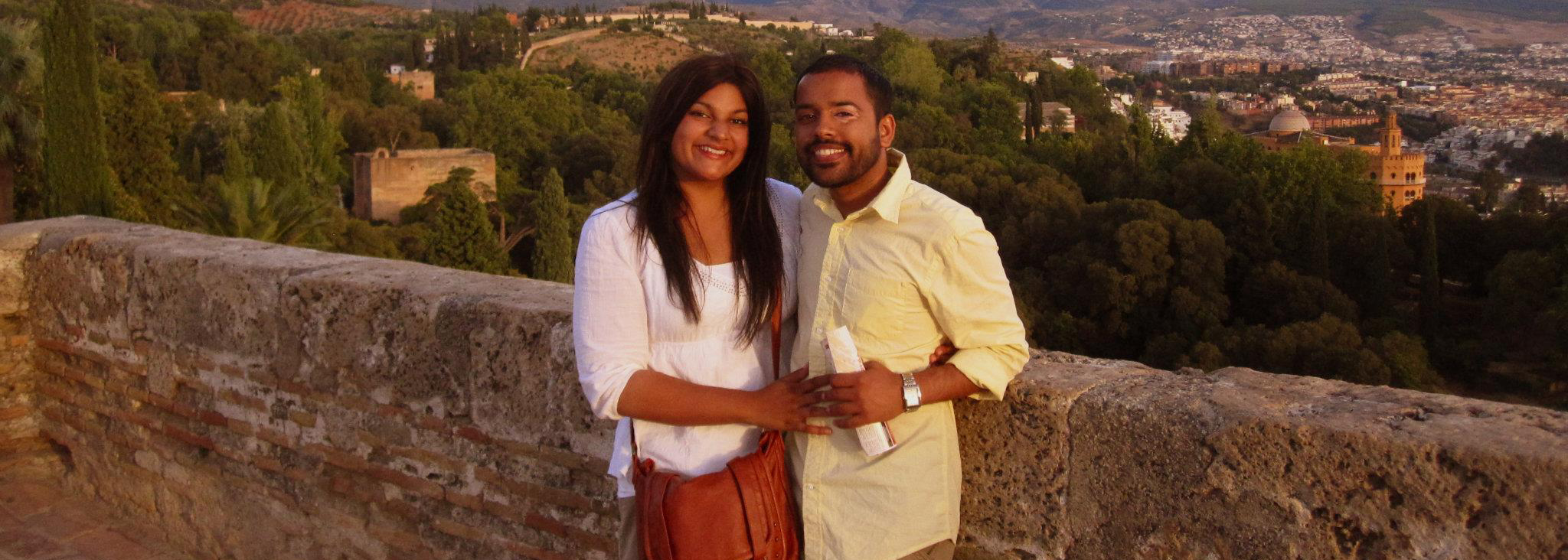

While still considered an experimental therapy decades later, the Clinical Center celebrates the milestone of this accomplishment in helping advance the science, motivate others in the medical field to continue the research and save lives. And of course this advancement couldn’t have happened without the incredible patients and families who participated in the clinical trial and are partners in research. At the age of just four-years-old, Ashanthi De Silva, was the first patient to receive gene therapy. Now, 25 years later, De Silva is “doing very well!” she said. “My husband and I will be celebrating our five-year anniversary in two weeks. Although I have experienced my fair share of hospitalizations and complications, it hasn’t kept me from traveling the world, completing my education, and living a full life with friends and family.”

De Silva has adenosine deaminase deficiency, a genetic disease that is one form of severe combined immunodeficiency. Her weakened immune system left her defenseless against infections from bacteria, viruses and fungi. Doctors in the Clinical Center used a modified virus to deliver the correct ADA gene to De Silva’s immune cells and to the cells of another nine-year old girl. Each girl was given repeated treatments over a period of two years.

When asked how she would describe gene therapy, De Silva said “Genes are codes of DNA that instruct our cells on how to survive and function. In the example of SCID-ADA patients, our DNA doesn’t properly code for a gene that allows us to make a certain enzyme, which helps us rid our blood of toxins. This is called a genetic mutation. Gene therapy is a treatment that attempts to ‘knock out’ or replace a genetic mutation in the cell’s DNA with a properly functioning copy of that gene. In order to perform gene therapy, the code for the gene must be known, and scientists must have developed the proper vector to hold the corrected gene as it travels to the cell.”

White blood cells, which help protect the body from infection, were taken from De Silva and the other patient through apheresis (a process that withdraws blood, separates the needed cells, and returns the remainder to the body). Under the direction of Clinical Center biologist Charles C. Carter, researchers then used the blood samples to isolate T lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, and expose them in the laboratory to a retrovirus modified to carry the normal ADA gene. The normal genes for making adenosine deaminase were inserted into the cells. After given a 4-day period to multiply and grow, the corrected cells were then reinjected into the girls.

“People often ask [what I recall from that time] — whether or not I actually remember September 14, 1990, the first day of gene therapy,” De Silva said. “When you are four-years-old you don’t have much of a choice in what you’re going to wear for the day, let alone whether or not you’d like to be the first in the world to receive groundbreaking medical treatment!”

“It took months before September 14, 1990 to collect my cells and watch them grow. On the day when the corrected cells were supposed to be infused back into my body, a room had been set up for press, and was filled with cameras and reporters. The doctors and my parents never took their eyes off me during the entire treatment. I was given stickers, balloons, toys, yet I never cracked a smile. It must have been a pleasure for all to work with me (ha!).”

While the pioneers of gene therapy, Dr. Michael Blaese, with NCI and Drs. Kenneth Culver, and Dr. W. French Anderson both with the NHLBI have since moved on from their work at NIH, another key team member still remains – 25 years later.

In 2015, Bonnie Sink, a clinical nurse specialist in the Blood Services Section of the Clinical Center Department of Transfusion Medicine, fondly reflected on September 1990 at her desk.

‘It was an exciting time,’ Sink said as she quickly located a folder marked gene therapy from her files spilling over with newspaper clippings and journal articles from 1990. “I was a registered nurse working in the apheresis clinic and I did the collections of the cells that they were going to then insert the gene into.”

“We did manual apheresis because [the girls] were so small we had to worry about the amount [of blood] you could take out, based on the size of the child. It was a lot different 25 years ago. It was very time consuming. Today most cellular collections use automated apheresis methods,” Sink said. “At the time it was a big accomplishment to be trying gene therapy. Looking back the biggest thing is that these girls are now young adults and are doing well. People with that disorder really did not have a very good prospect then. But they survived and have a good quality of life.”

The first gene therapy, as with all milestone that the Clinical Center creates for the health of Americans and those around the world, was created with a foundation of hope.

“In the end, it boils down to one word: hope. You have to have hope for your child’s life, and this is what my parents did. They hoped for the best. It wasn’t much of a choice – either try the new treatment, or wait until I fell ill with an infection I couldn’t fight off,” De Silva said. “I would say the award for bravery should be bestowed upon my incredibly strong parents. I am also incredibly thankful for the NIH, and the three doctors who pioneered gene therapy and gave me and countless others a chance to experience life. It’s difficult to fathom the countless, frustrating hours and sleepless nights that went in to this research, and for every second of it I am completely grateful. The NIH is America’s shining beacon, without a doubt. I have yet to receive more skilled and attentive health care anywhere.”