It's time to ask the hard questions about the future of work

Changes implemented over the pandemic can help us rethink our approach

At the October town hall meeting, I introduced the general topic of the “future of work” (hereafter abbreviated FoW). I indicated that as we have the opportunity to think about our work and our place of work because of the reduced need to focus on COVID-19, we have to think about all the work that we do. For the purposes of discussion, the work is divided into transactional work and relational work.

Transactional work may be thought of as “my” work. It represents my individual assignment and the specific work product on which my contributions to the NIH and the Clinical Center are assessed. The attributes of transactional work are enumerated in my performance plan and assessed in my performance appraisal. At least some of the elements of my transactional workload are readily measurable. My first premise is that we have managed to get pretty good at doing transactional work during the pandemic whether we are present in the workplace, working remotely or working in a hybrid fashion – sometimes here and sometimes remote.

On the other hand, relational work is “our” work or the work we do together. It represents my contributions to the transactional work of others and their contributions to mine. I don't think there is a better synonym for relational work than teamwork but teamwork is still too restrictive to encompass all aspects of relational work. For instance, my relational work includes contributions to workplace culture and climate; filling in for my supervisor when they are ill or on leave; problem-solving discussions in departmental and work unit meetings and teaching and coaching the latest accession to the workplace until they can function independently. Inherently more difficult to measure, it is also more difficult to hold any individual or individuals accountable when the products of relational work diminish or the quality of work performed is reduced. My second premise is that our relational work has not been accomplished so well during the pandemic, and we need to make certain that our strategies for the FoW account for the relational work that is crucial to organizational success.

In order to approach the FoW correctly, we must endure a significant period of critical assessment. Our own personal and work situations introduce undeniable biases into self-assessments. Most of us are familiar with 360-degree surveys. A 360-degree survey involves assessment by supervisors, direct reports and peers – up, down, left and right. Using the analogy of a family, a 360-degree survey would involve our parents, our children and our siblings – all first degree relatives. (I do not advocate 360-degree surveys in families, just trying to make a point.)

However, just as teamwork is a little too simplistic to describe relational work, a 360-degree survey is still too narrow to encompass our relational work. Even if we get thoughtful assessments from our supervisor (another member of the Clinical Center staff), our direct reports (also members of the CC staff) and our peers (yep, also members of the CC staff), we neglect crucial constituents. I will get to those in the conclusion of this piece, but the quickest way to make a problem too hard to solve is to make it so big and so complicated that we lose hope. So, let's start with a simple 360-degree assessment of our relational work. Here are the hard questions to get this assessment going.

Questions for all staff

- Is my supervisor satisfied with the quantity and quality of my transactional work?

- Is my supervisor readily accessible?

- Am I readily accessible to my supervisor?

- Am I fully abreast of individual and collective goals of my work unit?

- Are our staff meetings as productive in the virtual environment as when they were held face-to-face?

- Do my co-workers think I am pulling my weight, doing my fair share?

- If I am someone who has been in our work unit a while, am I able to lend my experience and expertise to co-workers who may be new? Am I accessible to them? How do they know I am accessible to them?

- Do I know what my co-workers are doing and what work priorities have been assigned to them?

- If I am new to the organization, do I have enough access to those who have been here longer that I have the opportunity to learn and grow and become an even more productive NIH'er?

- In well-developed teams able to telework very successfully, are there plans for when a shake-up in the team occurs due to promotion, retirement or sickness?

- Are team members willing to adjust their schedules as the team dynamics adjust to new and less familiar staff or even the same staff in new positions?

- What are the dimensions of inclusivity that are still important as we work in a distributed way?

Questions for supervisors

- If I am in the supervisory chain, do I have enough interaction with my supervisor that I can fill in for them if they are absent for one reason or another?

- If I am in the supervisory chain, have I passed along enough knowledge to those reporting to me so that one of them can fill in for me if I am absent for a period of time?

- If I am in the supervisory chain, do I have enough interaction with my direct reports that I know who is being successful and who is struggling?

- Do I know my direct reports well enough to know why they might be struggling?

- Do my direct reports know that I want them to be successful?

There are lots of questions and, in one way or another, they all have importance. However, I think these questions are only the starting point for the discussions that need to occur. If we go back to the analogy of the family, what happens when we extend the assessment to our extended family – all the cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents, etc. For instance, the questions listed do not address perceptions by the other NIH Institutes and Centers of our level of support while working from home or the perceptions of our patients and their families. The questions do not adequately describe the impact our physical presence or absence has on workplace climate and workplace culture.

But wait! There's more. While it is great to try to answer objectively questions about what is or isn't going as well while we telework, there is still the issue of whether, now that we are aware of the issues, we can get back to our pre-pandemic relational work productivity without all having to work onsite. What technology is available to us and will it help. My final premise is that technology helps enormously, but there are situations when it is a poor substitute for proximity and familiarity. No group of outstanding basketball players became a great team just by hours and hours of individual practice.

We will not solve the FoW conundrum once and for all anytime soon, but we start the process by identifying all the work we do, transactional and relational, and then asking all the hard questions. When we have answered those questions objectively and honestly, we have the beginning for understanding what the FoW is all about.

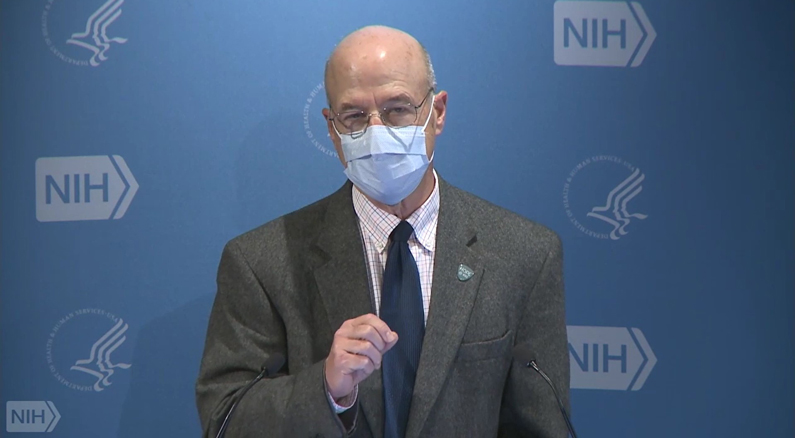

- Dr. James K. Gilman is the CEO of the NIH Clinical Center.